Exploring Seljuk Architecture in Konya

Let us imagine the Seljuks as a movement; an enormous influx of colossal bodies of water dashing from as far as the Far East carrying cultural sediments from the Central Asian Steppes, Transoxiana, Fertile Crescent, and Beth Nahrain, eventually emerging as a rich and generous delta of cultures that is united in the heart of Anatolia.

Throughout their gradual settlement in Asia Minor, Seljuks have created an idiosyncratic culture that developed unique types of expression, which would extend over the norms that could be found in an area that spanned between China and Anatolia.

In this blog, whenever we mention a new architectural form or an art feature they have introduced to the world’s cultural heritage, we should keep this movement in the back of our minds so that we can grasp the inimitable stance they hold in the world of heritage and comprehend what the remnants of their time represent.

But who were they? The Seljuks originated from Central Asian Turkic people, Oghuzs, who settled around the Aral Lake in the 10th century. Around the 1070s, when they founded their capital in Konya in Anatolia, they were still a semi-nomadic, semi-urban society. The nomadic Seljuks bore the cosmos in themselves: the nomads were bound to nowhere, they were the endless steppe on which they roamed, and with just an ephemeral settlement of a tent, the vastness was their home. Between the ground and the firmament, they were guided by a thousand spirits and signs. They were intermediaries, shamans.

The rest of the Seljuks were settled; they were the promoter of Islamic scholarly learning with the madrasas that they founded. They would also found the Stat-e, as they were now bound to the ground, stat-ic. However, their beliefs were not still orthodoxly established: with Sufi thinkers such as Muhyiddin ibn al-Arabi, Mevlâna Celâlalddin Rumi, Yunus Emre and Haci Bektaş Veli, the world was a stage for “a thousand and one appearances”, all leading to “a multiplicity in the One”. This somehow paralleled with the nomadic worldview, one’s place in the cosmic order was that of harmony, and it reflected profoundly onto the Seljuk art with geometrical shapes of various signs such as planetary systems, animal figures and vegetal motifs carved in perpetual patterns.

Examples such as a Qur’an stand, rahle, with a double-headed eagle and lion depictions, portal designs with Asian zodiac animals depicted in the intrados, or a bull and lion fight (figuratively “night and day”, “the moon and the sun”, constellations of Taurus and Leo, contrast between light and darkness etc.) the Seljuks showed the world a true liberal synthesis for a cultural unification.

This dual nature of the Seljuks endowed them with the property that would tell them apart from others: they had a high tolerance for urban societies, whereby they proved high adaptability to absorb characteristic elements from them, and thus, generated their own identity.

Despite the relatively short span of some 250 years, on a land full of intrigues and plots, a playground of power relationships crushed under external pressures and by internal strife, between the late 11th century and early 14th centuries, Seljuks undertook a rarely encountered, ambitious building programme - further taking it into account the age they lived. According to the registries, they covered Anatolia with about 1100 buildings, including 115 mosques, 144 masjids, 64 dervish convents, 145 tombs, 135 madrasas and medical schools, 15 dârülkurrâs (classrooms), 179 caravanserais (khan/hans), 70 public baths, 49 bridges, 24 fountains, and 48 palace-like places. 55% of the aforementioned still stand although some are heavily damaged.

This grandiose experiment is carried out by a total of 288 patrons all of whom are either sultans or state dignitaries; among the latter group there are also 34 women. Whereas as to the architects, draughtsmen, and other artists, among the 60 registered names it is seen that only 9 are based in Anatolia, the rest are of various provenances such as Armenians, Byzantines, Syrians, or Iranians. Employment of foreign artists and seeing their own cultural influences on the Seljuk designs suggest that the artist had relative freedom of expression on the Seljuk lands.

Konya is where the birth of a capital city occurred, and we are going to take you back to those times. Here, in this article, you will step inside a journey through the prominent Seljuk architectural marvels such as Alâeddin Mosque, Sâhib Ata Complex, Karatay Madrassa, İnce Minareli Madrasa, and Zazadin Caravanserai.

Then, without further ado, let’s see some examples from the Seljuk capital Konya!

Alâeddin Mosque

Alâeddin Mosque, with its greyish-blue-tiled mausoleum, is one of the most prominent images reposed on the Konya skyline. On top of an artificial mound that was once an acropolis, also possibly with the use of the spoila from the site, the construction of the Alâeddin Mosque began between the reigns of Mesud I and Kılıç Arslan II (c. 1155), as we know from the ebony minbar inside the mosque dating to that period, the first documented piece of Rûm Seljuk art in Anatolia. The construction of the mosque continued under Sultan İzzeddin Keykavus with the design by the architect Muhammed b. Havlâni from Damascus.

The minbar has its artist’s name and date carved in a panel, “by Mengi birti al Haji al-Akhlati (from Ahlat), in Rajab 550 (1155 CE)”. This minbar and its decorations speak to us in volumes. The infiniteness of the vegetal motifs complemented with lathwork rosettes and stars and an edging by Kufi calligraphy on the corners, both establish one’s position in the endlessness of cosmic being and also evokes harmony with it, a true master’s handiwork. Also, pay attention to the two artist’s provenance and how Seljuks tasked them with perhaps the most important building in their capital.

The mosque complex has two kümbets (or “türbe”s, tombs), one more graceful and intricate than the other. The first one is an octagonal-shaped, one-storey building and is left vacant. This incomplete structure is the only marble tomb tower built by the Seljuks.

It is known that the Sultan before Alâeddin was his brother İzzeddin, and the two brothers had a continuous feud, content or reasons of which are uncertain. The second, decagonal, two-storied, conical-roofed mausoleum - an allure to the “kurgan” model of the steppe tradition and synthesis with the Bagratid Gothic architecture - and its greyish-blue tiles are what strikes the eye when you first look from outside. Today, it is what is known as the “Mausoleum of the Sultans”, as all the Sultans from and after Kılıç Arslan II have their sarcophagus inside, except for İzzeddin; his is alone, most presumably relocated in Sivas, in the Divriği Great Mosque.

Sâhib-i Ata Complex

Sâhib Ata Fahreddin Ali was an important statesman that played a significant role in the Sultanate’s struggle under the Mongol invasions, the last phases of the Seljuks. During his 40-year of service, Sâhib Ata funded 18 buildings, second in line after Sultan Alâeddin Kaykubat I, who commissioned 26 buildings during his lifetime. Two of the architects who were employed for his complex (külliye) are documented as follows, Kālûyân el-Konevî and Kölük b. Abdullah. Sâhib Ata was himself from the el-Konevî family, but as to the identity of the second architect, let’s give it a pause for now.

Starting to be built around 1258, Sâhib-i Ata Mosque is a complex as it is composed of a mosque, a mausoleum, hankâh (guest’s room) and a hammam. One of the most striking architectural finesse of this structure can be observed in the portal with: richly decorated stone carvings on the corner niches for drinking fountains, stalactite muqarnas with Kufi calligraphy edged to the portal frame which is topped with an ornamental strip. The portal has one minaret standing, constructed with stonework, glazed bricks, and blue tiles. It is an important pioneer of the iconic two minaret portals in Seljuk architecture.

Further, when you move inside, the mausoleum (türbe), the hammam, and the hankâh will blind you with their dazzling splendour. Here you will find the most gorgeous images of stone, wood, brick, and tile works, arranged in both Turkish and Sufi world visions and suitable techniques. Also, fitted into the general complex, each of the mentioned has the Seljuk invention of four-iwan design, creating a sense of a world within a world, a type of fractal formation within the complex plan. Suggesting a balance in the whole space of being within the cosmic order. When you visit the hankâh section and its dome and see the perforated top, the mosaic-like composition of the tiles and bricks will induce a sense of Oneness with that order.

Unfortunately, the Sâhib-i Ata Complex has had to survive two catastrophic fires in the past. Nevertheless, its grandeur remains thanks to restitution works, and you will not be able to withdraw yourself from its magnetic pull once you see it.

İnce Minareli Madrasa

İnce Minareli Madrasa is another work built by Sâhib Ata, and its architect is again Kölük b. Abdullah. Abdullah being a traditionally generated name for those who are born to foreign heritage, and Kölük being similar in pronunciation to Koluk, it is suggested that the Armenian architect and stone master Galust (pronounced “Kaluk”) was the same person with Kölük. It is not surprising as many builders and masters from the Ani were employed under the Seljuk patronage after 1072.

When one looks at the madrasa portal, it can be seen that the façade is carved from stone with a Baroque manner, a form of elaborate and ornate art that would originate in Europe in the 16th century. With a spiralling Kufi strip and two symmetrical Trees of Life with a palmette root and affixed crescents, this decoration is directly in line with the Çifte Minareli Madrasa’s double-headed eagle figure with the Tree of Life. Except, the eagles in the İnce Minareli Madrasa’s portal seem to be abstracted by the curves of the top friezes. Further in the structure, the two-minaret design is repeated here as well. However, due to the tall design and a further force majeure by a lightning strike, the second minaret is again missing; hence the name, an “İnce Minareli", a structure with a singular “graceful/slender minaret". The exterior of the building is made of stone, and the interior is of brick.

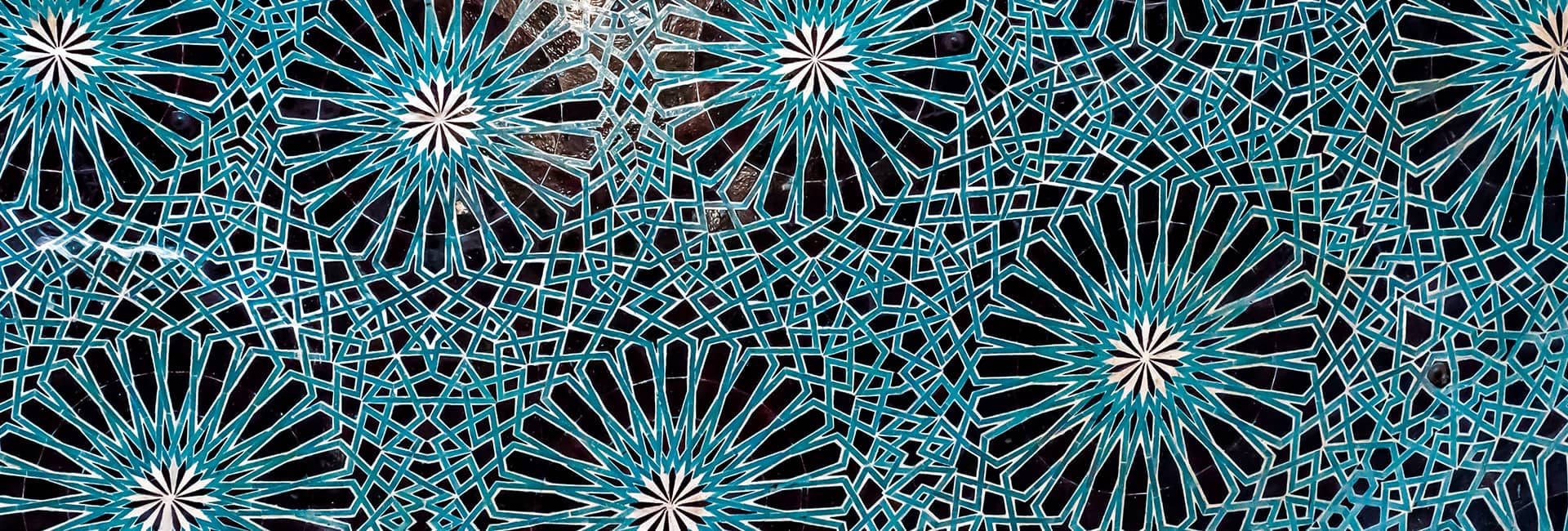

The dome is decorated by the arrangement of glazed bricks in turquoise, brown and dark blue colours to form endless geometric motifs. The intertwined zigzags and baklava motifs created by the vertical arrangement of glazed bricks resemble Turkish rug motifs. The phrase "al-mulku lillah" (All that there is belongs to God) is repeated with a knitted Kufic script made of turquoise-coloured tiles on the wide trunk that surrounds the dome drum, where the dome top used to be a giant roof lantern.

In terms of use, a madrasa was a school of theology, initially founded by the Great Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk to standardize Islamic education. Acting as a boarded school, these buildings had rooms to host pupils, which can be observed here as well.

Also, today, one part of the İnce Minareli is partitioned to host a Stone and Wooden Works Museum, so make sure to spare time to visit it as well!

Karatay Madrasa

Karatay Madrasa is quite similar to İnce Minareli; however, it has a more modest portal and a more opulent interior. This, however, cannot diminish the expressive pose the portal can induce. In addendum to the previous portals, Karatay Madrasa also uses a muqarnas, a vaulting design that is created by hollowed-out stalactites at the entrance of the portal. It is also fascinating that the grey and white marble inlay strip, just like the one on the Alaeddin Mosque portal is added to the Karatay Medrese, suggesting a close relationship between the two structures, especially given that the Karatay Madrasa’s architect is unknown. Nevertheless, the similar knitting patterns are thought to be a Syrian knot motif: remember Muhammed b. Havlâni from Damascus?

This madrasa is known to be one of the few definitely identified to be commissioned by another Seljuk vizier, Celâleddin Karatay. Karatay is generally accepted to be a loved-by-all figure and mentioned with respect in both Muslim and non-Muslim accounts. Karatay Madrasa is one of the three madrasas built by the statesman; however, as it was part of Karatay’s modest character, he did not want his name written anywhere unless he was asked for, displaying a strong and generous disposition which would rather opt for remaining anonymous, declining any credit.

The madrasa dome is decorated on four corners by prophet names and the dome drum is circled again by calligraphy. The pendentive dome structure and the related decorations led scholars to think it to be in line with the idea of a universal tent, a compromise between Sufism and Steppe traditions.

Today, some parts of the madrasa are reserved for the Tiles Section of the Konya Museum, where you can continue exploring in detail the great Seljuk tile-works and craftsmanship.

Zazadin Han (Caravanserai)

In the past, travel was quite an undertaking yet it was necessary for communication, trading purposes and pilgrimage. Arguably, the biggest risk group was that of the merchants, as they not only had their lives to lose, but also their trade goods, personal belongings, and animals. Therefore, to establish safe passage between one location to another, Seljuks developed the form caravanserai (literally, a palace for the caravan), or simply (k)han. These would be built at intervals which a caravan is expected to cover in a single day, about 30 km. The facilities would provide three days of free-of-charge shelter and food services; further, equipped with partitions to carry out religious practices, they would also employ a wide range of people from different professions such as religious officials, cooks, blacksmiths, tailors, veterinaries, cobblers etc. And if one looks at them from afar, due to the architecture, it is possible to mistake them for castles, implying the value attached to these buildings.

It is known that such facilities existed before the Seljuks, but in terms of scale, design, functions, and services provided these were unprecedented. Indeed, trading activity was so much valued that ever since Seljuks first got a hold of Anatolia, they gave incentives to both Muslim and non-Muslim traders, reduced taxes, established rights of free movement, and provided indemnification if the merchants were harmed during their journey. Moreover, the caravan route between Denizli-Ağrı (Doğubayazıt), some 2500 km trading road, also included in UNESCO Tentative List, being covered by 179 known hans, is a gigantic number even for today.

Our Han is called Zazadin Han, built by another state official called “Sâdeddin” Muhammed b. Köpek; as the locals would not be able to pronounce the foreign word “Sâdeddin” adequately, the name rendered to be “Zazadin” in the dialect. Köpek is also an interesting figure that merits our attention. We know that he was employed by Alâeddin Keykubat I as an architect to build a now-in-ruin palace called Kubâdâbâd, near Lake Beyşehir. However, how he came to be a vizier is unknown. During his time, Köpek was described as a "blight on the land" figure for the state officials; nevertheless, he was favoured by locals.

Köpek was among the supporters of Gıyâseddin Keyhusrev II to take the throne; however, soon, he would accumulate too much power whereby start eliminating state officials including an Atabeg (governor), a Vizier, and a Seljuk General. With an assertion that he was an illegitimate child of Keyhusrev I, he attempted to claim the throne. He was soon assassinated in an arranged festivity by the order of Keyhusrev II. When you visit Zazadin Han, use your imagination and see how much power he exerted during his time with his only building, the biggest caravanserai in Konya!

To learn more about Konya, please click here and if you want to further explore architecture in Anatolia, click here.